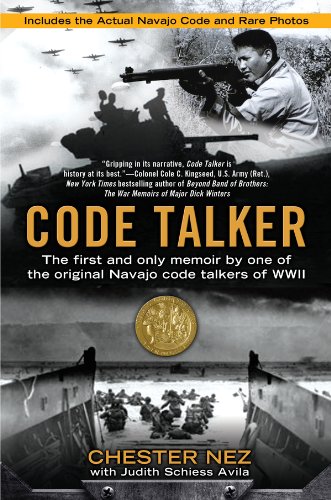

The first and only memoir by one of the original Navajo code talkers of WWII

By Chester Nez with Judith Schiess Avila

Civil engineer Philip Johnston, the son of a missionary couple, grew up on the Navajo Reservation. He is credited with proposing the idea for the secret Navajo mission. He convinced Marine brass that the Navajo language–unwritten, and spoken by only those who had lived with us Navajos–could become the basis for an unbreakable code.

Since the language was not written, it couldn’t be learned from a book.’ It was estimated that only thirty non-Navajos spoke our language. Even that estimate was contested by many Diné, who believed that the complex could be learned only if one began in infancy. Johnston himself was a fine testimonial to this belief. Although he’d moved to the Navajo Reservation at the age of four with his parents, and although his playmates were all Navajo, he had learned the language only well enough to be considered a speaker of “trader” Navajo. He never became truly conversant with the deeper complexities of the language.

Pronunciation of even one Navajo word is nearly impossible for someone not used to hearing the sounds that make up the language. During his first year of life, a baby grows accustomed to the auditory variations from which his native language is composed. As time goes on, children become less able to distinguish sounds from unfamiliar languages. Thus it is difficult for a non-Navajo speaker to hear Navajo words properly, and virtually impossible for him to reproduce those words.

Native American languages, notably Choctaw and Comanche, had been used in a very limited way during World War I. In Europe, Native American fighting men were asked to transmit messages in their complex languages in order to stymie the enemy. This effort involved no code, but was an on-the-fly idea utilized only by several innovative commanders. After the war, the Germans discovered which native languages had been employed, and they sent “tourists,” “scholars,” and “anthropologists” to many tribes in the United States to learn their languages. Navajos were not among those tribes. That, too, worked in favor of using our Navajo language in developing a code. And we had another advantage. We had resisted adopting English words and folding them into our language. We made up our own words for new inventions, things like radios and telephones, keeping our language pure and free of outside influence.

(Nez and Avila 2011, 90-92)

Navajo bears little resemblance to English. When a Navajo asks whether you speak his language, he uses these words: “Do you hear Navajo?” Words must be heard before they can be spoken. Many of the sounds in Navajo are impossible for the unpracticed ear to distinguish.The inability of most people to hear Navajo was a solid plus when it came to devising our code.

The Navajo language is very exact, with fine shades of meaning that are missing in English. Our language illustrates the Diné’s relationship to nature. Everything that happens in our lives happens in relationship to the world that surrounds us. The language reflects the importance of how we and various objects interact. For example, the form of the verb “to dump something” that is used depends upon the object that is being dumped and the container that is being utilized. If one dumps coal from a bucket, for instance, the verb is different from the verb used to describe dumping water from a pail. And the verb again differs when one dumps something from a sack. Again, in Navajo you do not simply “pick up” an object. Depending on what the object is—its consistency and its shape—the verb used for “to pick up” will differ. Thus the verb for picking up a handful of squishy mud differs from the verb used for picking up a stick.

Pronunciation, too, is complex. Navajo is a tonal language with four tones: high, low, rising, and falling. The tone used can completely change the meaning of a word. The words for “medicine” and “mouth” are pronounced in the same way, but they are differentiated by tone.? Glottal and aspirated stops are also employed. Given these complexities, native speakers of any other language are generally unable to properly pronounce most Navajo words.

But the complexities of the Navajo language provide a wonderful tool for spinning tales. Our speech does not simply state facts; it paints pictures. Spoken in Navajo, the phrase “I am hungry” becomes “Hunger is hurting me.”

The conjugation of verbs in Navajo is also complex. There is a verb form for one person performing an action, a different form of the verb for two people, and a third form for more than two people.

English can be spoken sloppily and still be understood. Not so with the Navajo language. So, even though our assigned task-developing a code-made us nervous, we realized that we brought the right skills to the job.

(Nez and Avila 2011, 104-108)

The old Shackle communications system took so long to encode and decode, and it was so frequently inaccurate, that using it for the transmission of on-the-fly target coordinates was a perilous proposition. Frequently, in the midst of battle, instead of using the Shackle code, the Marines had transmitted in English. They knew the transmissions were probably being monitored by the Japanese, so they salted the messages liberally with profanity, hoping to confuse the enemy.

We code talkers changed all that.

(Nez and Avila 2011, 136)

“Men, you’ve done an excellent job.” He stopped, cleared his throat.”I’m afraid we can’t afford to let you go. You are vital to the success of this campaign. The Second Marine Division still needs you men here.”

Heavy silence settled over us. This was war. Any argument was useless, and we knew it. I looked across the beach, littered with the broken and worn-out equipment of war. I felt just as worn out as those useless vehicles and broken-up gun emplacements. But a used code talker couldn’t be replaced by a new model of the factory floor. And there were too few of us to expect replacements the way other infantrymen could expect them. It was a crushing disappointment, not to be leaving with the rest of our division. We’d made good friends on the battlefield, where everyone depends on his buddies. It would be hard to see them leave while we stayed with the 2d Marine Division.

But we had no choice. We got ourselves squared away. We resolved to keep fighting.

(Nez and Avila 2011, 151)

References

Nez, Chester, and Judith S. Avila. 2011. Code Talker. N.p.: Berkley Caliber.

ISBN 978-0-425-24423-4

Leave a comment